The Official (Sometimes Guilt-Ridden) Blog of Leonardo Ciampa

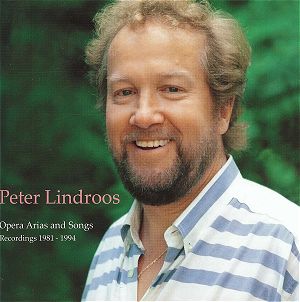

PETER LINDROOS AND HIS PLACE AMONG THE GREAT TENORS

by Leonardo Ciampa

There is an important difference between publicity in the Caruso era and publicity in the Pavarotti era. Caruso did not have a manager. Caruso didn't “become” the greatest tenor in the world, because he already was the greatest tenor in the world. There were no dissenting opinions. No one in Caruso's day said, “Caruso wasn't that good; he was just OK.” Everyone agreed that he was the greatest – critics, colleagues, public.

Pavarotti had a manager named Breslin. Thanks to the hard work of Breslin, Pavarotti “became” the greatest tenor in the world. Unfortunately, no singer, no critic, no musician – no one who knew anything about singing – believed that he was the greatest. The public believed what they were told. However, they were not given the option of comparison. Had Breslin lined up Pavarotti, Aragall, Gedda, Kraus, and fifteen other tenors, would the public still have voted Pavarotti the greatest? In such a survey, probably Pavarotti would have come in last.

I needed hear only a few minutes of Lindroos's singing to know that he was one of the greatest tenors in the world. He had everything – great voice, great technique, great musicianship, great expression. He was great in every respect that a tenor ought be great.

So why didn't Lindroos become more famous?

Invariably, when one person becomes famous and another of equal talent does not, the reason has nothing to do with music. Events occur. Choices are made. I am not Lindroos's biographer; I am not equipped to explain why his life's path did not take him to the Metropolitan. If I were the director of the Metropolitan and I heard Lindroos sing for a few minutes, I would have said, “He is a very great singer; he shall sing here.” However, the fact that I have an ear does not, in itself, earn me the title, “Director of the Metropolitan.” In fact, having an ear counts for virtually nothing.

The other problem is that overall musicianship is not marketable. If you are a pianist who plays two piano concertos without wrong notes, you can get a New York manager and play 100 concerto performances a year, playing each concerto 50 times. If, instead, you are a composer and an organist and a pianist and a conductor and also a singer, what can a New York manager do with that? How does the manager market you? The better a musician you are, the worse (not better, worse) chance you have of being world-famous. J. S. Bach would not have been world-famous in the 20th century, because no manager in New York would have gone near him.

Rather than dwell on what the world did not recognize, let me dwell on what I do recognize. I recognize that Lindroos had everything. He was one of the most satisfying tenors in the world – satisfying because it was impossible to say, “Something is lacking.” The voice itself was remarkable in its beauty – a beauty that only a Scandinavian voice can have. His diction was formidable; he sang complete operas in eight languages. His technique was that of the great singers of previous generations. In fact, I don't think the Metropolitan would have appreciated his vocal production, which was more akin to the tenors of the 1920s than to those of the 1970s. However, the 1920s technique allows one to sing 1700 operatic performances (which Lindroos did); the 1970s technique does not. Lindroos's musicianship was very strong and imbued every note he sang. His humanity was very rich – he felt the highs, he felt the lows, and this depth of feeling created a wide palette of emotional colors with which he could paint his characters. All of these traits – voice, technique, diction, musicianship, humanity, and Scandinavian genes – combined to produce a tenor, next to whom the Pavarottis and Domingos seem to be utter charlatans.

It is of crucial importance that all of the recordings of Peter Lindroos be made available – so that musicians can study them, and so that music lovers can be blessed by them.

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

On Sunday, January 16, 2011, at 4 p.m., DAVID BRIGGS, organist emeritus of Gloucester Cathedral, England, and one of the world's greatest concert organists, will give an organ recital at MIT Kresge Auditorium – the first important organ recital in that hall in almost four decades. Admission for this historic event is FREE.

On Sunday, January 16, 2011, at 4 p.m., DAVID BRIGGS, organist emeritus of Gloucester Cathedral, England, and one of the world's greatest concert organists, will give an organ recital at MIT Kresge Auditorium – the first important organ recital in that hall in almost four decades. Admission for this historic event is FREE.

The organ in MIT's Kresge Auditorium was installed in 1955 by Walter Holtkamp, Sr. The consultant was Melville Smith, a well-known leader in the Organ Reform movement. During the eras of Smith and of Canadian organist/composer John Cook, who was the MIT Organist in the 1960s, many organists of international renown played recitals in Kresge: Marchal, Heiller, Cochereau, Biggs, and others. However, it's been almost 40 years since a world-class organist has played a recital in Kresge – until now. David Briggs's recital on January 16, 2011, at 4 p.m. is a historic event, featuring one of the most brilliant organist/composer/improvisers in the entire world. The program will include a grand improvisation entitled “Kresge Reawakened,” a four-movement improvised symphony, based on submitted themes.

For this historic event, the admission is FREE.

This concert is being sponsored by the MIT Office of Religious Life (Robert M. Randolph, Chaplain to the Institute.)

For more information, contact Leonardo Ciampa, Artistic Director of the MIT organ concert series (leonardociampa@hotmail.com).

AN INTERVIEW WITH DAVID BRIGGS

Leonardo Ciampa: We’re thrilled to be welcoming you to play at Kresge Auditorium! Can you tell us a little about your career as an organist? At what age did you start to play?

David Briggs: I’ve played the organ since I was six, although I didn’t have any lessons until the age of twelve (after I’d reached a fairly high level on the piano and my feet could properly reach the pedals). I’m delighted to be performing on the Holtkamp Organ here at MIT. In fact I played my first ever concert in the USA on a Holtkamp instrument – it was at the Church of the Covenant in Cleveland, Ohio in February, 1997. I remember five inches of lake-effect snow fell during the course of the concert and I improvised on “Rudolph, the Red-Nosed Reindeer.” Coming from the UK, I remember immediately being very impressed by the size and generosity of US audiences, as well as the huge automobiles, not to mention the fact that everybody spoke with a strange accent and drove on the wrong side of the road. I couldn’t have predicted that I would be (very happily) based in this country from 2003.

LC: What made you want to start the organ?

DB: My grandfather was a well-known organist in Birmingham and I used to go and sit on the bench with him (aged 6). His teacher was G. D. Cunningham, the famous predecessor of Thomas Trotter and Sir George Thalben-Ball [and the teacher of E. Power Biggs]. My dad used to take me to New Street Station to see the Deltics (in the sermon!). When I was nine, I became a chorister at St Philip’s Cathedral, Birmingham, under Roy Massey. It was at that period that I really decided I wanted to be an organist. Roy’s marvelous playing (and also the brilliant improvisations of John Pryer, the Assistant Organist) really inspired me. I even had some planks of wood either side of pedals on our grand piano at home made out with pedal pistons inscribed – including (of course) Bombarde 32’ (reversible) and Full Tubas (solo).

When I was a Music Scholar at Solihull School, I came under the influence of Colin Edmundson, who had been a Domus Music Scholar at Magdalen College, Oxford, under Bernard Rose. Colin was an extremely inspirational teacher, who encouraged a strong sense of rigour and single-mindedness. At one point there were four schoolboy FRCOs at Solihull – surely something of a record.

Finally, when I was sixteen, I studied in London with Richard Popplewell, at the Chapel Royal. Richard was a fabulous and very generous teacher as well as an extremely kind person. I lost my father when I was sixteen, and Richard in many ways took over. I owe him a huge amount.

LC: What are your principal philosophies of performance?

DB: Nowadays I only play pieces which I really love, and I always try to communicate to the audience, “Look, guys, I think this really is one of the best pieces of music that’s ever been written.” From a technical point of view, I try and balance making things as streamlined and dovetailed as possible with taking some risks and being impulsive. It made a big impact on me when, as a 12 year old, I heard the great cellist Paul Tortelier say in a masterclass, “The biggest crime is to be boring.” If there are a few wrong notes, I always mentally try to move on – reboot my computer, so to speak. I loved it when the great Swiss organist Lionel Rogg once explained to me, in a competition debriefing, “I never mind playing a few wrong notes … because I know I will have made someone happy.”

Regarding authenticity, I think it’s very important to keep a clear overview of the sweep of the music not get too involved in minutiae. Having said that, I sometimes use some elements of Baroque fingering and pedaling, coming from having played quite a few historic instruments in Holland and Germany, but more often say to myself, “Well, just try to make it sound as it would if played by a Baroque oboist, cellist, or whatever.” I’m big on listening to other musicians/singers and learning how I can make my own performances more convincing and expressive.

LC: What are your philosophies of improvisation?

DB: I would say that you’re always trying to give the illusion of a written piece, but the sheer spontaneity and ephemeral nature of the art can give a good improvisation an edge over the performance of a previously-composed piece. Most jazz musicians would certainly agree with that statement. I have always found it easier to improvise than to play written pieces, for some reason. Maybe it’s to do with the way the human brain is hard-wired. It has something to do with being totally at home with the musical language which surrounds you and then being able to re-fashion it, subconsciously and at will. Good improvisers have usually always been so, rather like good composers. It’s a matter of gift, environment and (of course) training. There are certainly parallels between good improvisers and good mimics … in terms of in-depth assimilation of syntax, grammar and characterization. I also believe that the ability to improvise well helps you to “lift the music off the surface of the page” when performing repertoire. That can make a very big difference.

LC: What are your views on organbuilding?

DB: My favourite instruments are in France and my favourite organ in the world has always been the Grand Orgue of Notre-Dame de Paris.

I used to be skeptical about people who talked endlessly about mechanical action – but the more instruments I have played, the more I realise that the type of action can actually make a big difference. There is nothing like the reality of a finely-balanced mechanical action. I remember an interview with Glenn Gould talking around the issue of piano vs. harpsichord, when playing Bach. He said that he always chose piano, because of the sensitivity of a modern Steinway action – it allowed him to express much more of what he wanted to say in the music. Having said that, of course many very large instruments would not be so good (or even possible) with mechanical action. Barker lever (and the Servo-assisted pneumatic action, patented by Fisk) can also be very satisfying.

In general terms, I think the best instruments are those with very well-blended pipework and an action which is fast, both in attack and release. The best electric action instrument I’ve played (every day for 8 years) is at Gloucester Cathedral. That is almost as responsive as a mechanical action instrument.

LC: Apart from Notre-Dame, which are your other favorite instruments, and why?

DB: I particularly enjoy playing on the big, symphonic instruments over here in the USA. There is something about the banks and banks of American strings which I love, especially with liberal use of octave couplers! With so many swell boxes, it’s possible to make virtually seamless crescendi and diminuendi, especially good for transcriptions.

I mentioned the Gloucester organ, earlier on. This is a really wonderful sound, greatly aided, of course, by the unique eight-second acoustic. Gloucester had a big influence on the way I played (particularly improvised). It is a very eclectic instrument, playing all styles with a good integrity. Bach sounds marvelous on it, as does French Classical, Romantic and Modern music. And I think it also accompanies very well, … it’s very clear for the choir to hear, and there is a lot of colour (especially if you’re slightly unorthodox in the way you register!). When I left Gloucester in 2002, I thought I would miss it terribly, but that wasn’t really the case. When you bond with an instrument like that over eight years, it becomes part of you and you take it around in your imagination. But I always love going back there.

For six years I had the privilege of having daily contact with the Father Willis organ at Truro Cathedral. I believe it’s the best of the Willis’s, with Salisbury and Hereford close coming in a close second. Truro has the advantage of great presence in the building (owing to its excellent position). The Truro Willis has a unique character, and is so musical. It can be incredibly fiery, too – I used to liken it to a Ferrari, whereas Hereford (where I was Assistant before moving to Truro) is more like an old Bentley (more plush…).

I was Organ Scholar at King’s College, Cambridge and the Harrison Organ there is marvelous at what it does best – accompanying. I think the most beautiful organ stop in the world has to be the Claribel Flute on the Choir Organ – pure velvet.

Recently, I’ve done a lot of playing in Germany and have very much enjoyed the instruments there – always in great acoustics. I really admire the organ culture in that country, too – very good publicity (colour posters, etc) and consequently sizeable, intelligent and enthusiastic audiences (including a lot of young people).

The best organ I ever played in the Southern Hemisphere was the five-manual Hill at Sydney Town Hall – a really great experience. I remember playing a Bach Fugue on forty-four 8fts, all coupled. Wonderfully inauthentic, but fabulous, all the same.

LC: What is your favorite repertoire and what is your approach to learning and performing it?

DB: I love playing the French Symphonic repertoire and think that is suited well to my temperament (whatever that is!). I studied with Jean Langlais for two years in Paris and that was a marvelous experience. Langlais was incredibly fussy and fastidious (I remember spending 30 minutes on the first 8 bars of the Franck Fantaisie en la) – but also very affirming. He was a genius at improvisation pedagogy – we worked a lot at that, concentrating on modes, harmony, form, counterpoint etc. People used to say that Langlais “could make stones improvise.” The other thing he said to me once was that “it takes fifteen years to learn how to improvise.” I think he’s probably about right.

LC: Who are your favorite composers, and why?

DB: I think the composer I really couldn’t live without is Gustav Mahler. His symphonies are so life-giving and enriching. One of the greatest experiences I ever had was playing the Viola in Mahler 5, during my four years in the National Youth Orchestra. I become very emotionally involved – it was inescapable! Later I transcribed (and recorded) Mahler 5 and Mahler 6 for organ, and am now engaged on a similar project – Mahler 3. Other composers who are very important to me are Debussy, Ravel, Poulenc, Scriabin and Strauss. I actually much prefer going to symphony concerts than organ recitals, and we try and hear the Boston Symphony as often as possible. Recently I went to a rehearsal of Scriabin “Le divin poeme” with Riccardo Muti – I was transported to another world.

LC: Who have been the most major influences on you? Who are your heroes?

DB: Pierre Cochereau. Cochereau was Organist of Notre-Dame from 1955-1984 and a very generous human being, as well as generous musician and (in my opinion) there has never been anyone come close to him as an improviser. I spent eleven years transcribing many of his famous improvisations from Notre-Dame, which were released on the Solstice label. His harmonic style, although closely related to that of his teachers Dupré and Duruflé, was so original and so evolved. For twenty years, I listened to Cochereau every day. Although I never met Pierre Cochereau, I feel quite close to him in spirit.

LC: What would you say if someone asked you to transcribe one of your improvisations?

DB: I would tell them that I think they should definitely get out more.

LC: Do you have any advice to young aspiring organists?

DB: Make sure that you have quite a good piano technique before starting the organ. I know that’s a contentious point, but I think it’s critical – especially if you want to go above a certain level of expertise. The other thing is to learn how to practice well – set yourself continual and obtainable challenges and make your time at the instrument as efficient as possible. I do about 75% of my practice on three or four coupled 8fts, and then enjoy playing louder once I can play the notes. Practising with the metronome can also be very hypnotic – except that the metronome I have never seems to keep with what I’m playing!

In an ideal world, it’s good to learn a piece several months before you play it in public, and then put it to bed for a few weeks. Mind you, like most people, I’m always “up to the wire” so that approach doesn’t always seem to fall into my lap. Interestingly, I’ve found that British Organists are the best in the world at coping with putting things together at the last minute. In the USA, organists seem to take much longer to get things under their belt. It’s interesting that Pierre Cochereau once said that he found it very difficult to sight read. … I guess it’s all a question of pedagogical emphasis. In the UK, Organ Scholars have to play (and learn) a different Magnificat and Nunc Dimittis every day.

LC: MIT is synonymous with science and engineering and not music. How and why do you think organ music relates to or is important to science?

DB: The organ is the largest and most complex of all musical instruments. Many large instruments have hundreds of thousands of moving parts and tens of thousands of pipes. Each mechanical part (be it wind reservoir, pallet magnet or wind stabiliser) has to work perfectly over a long period, and each pipe has to be voiced to blend to the rest. The finest organs are those which represent an ideal synthesis between artistic vision and technical prowess. In other words, the very best instruments are the result of many, many hours of skilled workmanship in terms of pipe voicing, sophistication of key action, stability of voicing, excellence of acoustic and so on. Then you have a true meeting of science and music. Playing on such a large variety of instruments is a very enriching experience – each time you have to ‘learn’ the instrument because organs are so different to each other.

TEN DAYS IN THE LIFE OF DAVID BRIGGS (November, 2010)

Wednesday 10th: Depart Ipswich at 6.45am for the Peabody Shuttle to Logan Airport. Check-in for the London flight, listening to Mahler 3 on Bose Headphones. Get some quite funny looks as I conduct with one hand and wheel my suitcase with the other. Enjoy the American Airlines Admirals lounge and try not to think about the calorific implications of having two breakfasts. Board AA156 and enjoy the customary whiff of Aviation Fuel as you walk over the jet bridge. 15 minutes after take-off spool up laptop and work on the Gloria of my new Messe pour Saint Sulpice for 5 hours (courtesy AA laptop power – Deo gratias). Get more strange looks and am asked if I’m a composer by friendly AA lady flight attendant: “Do you compose rock?”, she asks. “Umm, kind of” I reply in an excessively British accent. “That’s so cool… can I get you any more cwa-fee?”. Arrive at Heathrow, cruise through Customs, wait 30 minutes for a Hotel Hoppa minibus. Credit Card ticket machine broken. Wait for another bus after the first one brakes down. Check into hotel: Wifi connection bust. Welcome back to England.

Thursday 11th: Check-in to British Airways flight to Milan. Fabulous views of Central London flying out of Heathrow. Enjoy seeing England and France at the same time from 33,000 feet (rather like some of my music, some have commented). Observe Paris, looking resplendent from such a great height. Thoughts of ever-present musical inspiration from those hallowed organ tribunes, not to mention on-going love affair with my beautiful wife. Descend over the breathtaking Italian Alps and arrive into Milan Malpensa – a rather faded glory airport. Take bus into Milan (60 minutes) – listen to Cochereau Improvisations on iPod. Transfer to train at Milan Central and arrive at Piacenza in thick fog at 11:30pm. Nobody speaks English – walk to hotel with heavy case, 120 CDs, computer bag and iPod. Feel virtuous about the rather high reading on my iPod’s pedometer. Check into Piacenza Hotel. Owner looks exactly like Sir Edward Elgar reincarnated and runs the hotel rather like Faulty Towers.

Friday 12th: Marvel in the beauty of Italy. Not a single right angle in sight in these beautiful buildings. Visit five different churches, dating from the 11th to the 20th centuries. Struck by the sincerity of Roman Catholics as they light their candles, unaware of those around them. Enjoy fabulous Italian café espresso and rather inviting patisserie. Compose more in the hotel. Rehearse for 3 hours on the two-manual Tamburini in the Church where I am performing – the best stop on the organ is the beautiful acoustic. Catch up with some more silly commentary on Facebook and email. Compose more on laptop.

Saturday 13th: Rehearse again at the church, visit the Saturday market, humming with vitality and passion. Admire the Italian life-style, especially the ubiquitous two-hour close down and seemingly obligatory vino rosso consumption at lunchtime. Concert at 9pm, starts at 9.25pm (normal in this part of the world) and ends at 11.15pm. Go to somewhat esoteric fish restaurant with Concert organizers. Return to Hotel at 1:25am.

Sunday 14th: Stagger out of hotel at 6.30am, pull suitcases along frosty, bumpy Italian pavements to the railway station and take express train back to Milan. Fly back to Gatwick and spend very enjoyable day with my two wonderful British daughters in West Sussex. Drive three hours to Cambridge.

Monday 15th: Check in to my rooms at Trinity College at midnight. Arise and take a walk on the Backs – the air is supersaturated with ice and the quality of the light reminds me of my days as a student nearly thirty years ago. Teach at Jesus College in the morning, Trinity in the afternoon and at Girton in the evening.

Tuesday 16th: More teaching (Improvisation techniques and repertoire), followed by High Table at Trinity. Judging by the stunning 1968 wines and Taylors Reserve Port, the Credit Crunch has yet to reach Cambridge.

Wednesday 17th: Drive from Cambridge to Stansted Airport and take the Easyjet Flight to Edinburgh. An agreeably turbulent landing, due to 30mph windgusts across the runway. Picked up at the airport and proceed to bed and breakfast near Loretto College. Wonder why the Scots never switch on their central heating. The owner of the bed and breakfast proudly explains that he’s just past his 93rd birthday. I wonder if it must be resilience caused by the lack of central heating. Everything seems rather grey and infused by uninviting cups-of-tea (or whisky …).

Thursday 18th: Teach masterclass at Loretto (mainly beginners, but very therapeutic) and play silent movie concert “King of Kings” (Cecil B. DeMille). Escape into my private zone with more work on Messe pour Saint Sulpice.

Friday 19th: Fly from Edinburgh to London Heathrow, collect hire car, drive to Hereford. Mapquest says it should take 3 hours – takes 5 due to freezing fog and three major holdups due to accidents on the M4 and A40. Give re-opening concert of the organ in Belmont Abbey after a rather scanty 45 minutes rehearsal – very full church and quite enthusiastic reactions. Am amazed by the lavish reception in the intermission – wonder if the monks live it up like this often?

Saturday 20th: Drive to Birmingham to visit my wonderful mum, her partner David and my sister and my friendly and musical nieces.

Sunday 21st: 20th birthday lunch in Birmingham for my beautiful daughter Kerensa Briggs.

Monday 22nd: Shopping in Bristol and dinner in Birmingham

Tuesday 23rd: depart Birmingham at 6am, drive to London Heathrow and catch American Airlines flight to Boston. Compose for five hours en route.

Kresge Auditorium

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Cambridge, MA

Celebrity Organ Recital

By

DAVID BRIGGS

Organist Emeritus, Gloucester Cathedral

Sunday 16th January 2011 at 4pm

PROGRAM

Toccata: Tu es Petra Henri Mulet (1878-1967)

Scherzetto (Sonata in C minor) Percy Whitlock (1903-1946)

Piece d'Orgue, BWV 572 J S Bach (1685-1750)

Romance (Symphonie 4) Louis Vierne (1870-1937)

Carillon de Westminster (Pièces de Fantaisie)

Vocalise Serge Rachmaninoff (1873-1943) arr. DJB

Prelude and Fugue in B major, Opus 7 No 1 Marcel Dupré (1886-1971)

INTERMISSION

“Kresge Reawakened” – Improvised Symphony in Four Movements (on submitted themes)

David Briggs is an internationally renowned organist whose performances are acclaimed for their musicality, virtuosity, and ability to excite and engage audiences of all ages. With an extensive repertoire spanning five centuries, he is increasingly known for his brilliant organ transcriptions of symphonic music by composers such as Mahler, Schubert, Tchaikovsky, Elgar, Bruckner, Ravel, and Bach. Fascinated by the art of Improvisation since a child, David also frequently performs improvisations to silent films such as Phantom of the Opera, Hunchback of Notre-Dame, Nosferatu, Jeanne d’Arc, Metropolis, as well as a variety of Charlie Chaplin films.

At the age of 17, David obtained his FRCO (Fellow of the Royal College of Organists) diploma, winning the Silver Medal of the Worshipful Company of Musicians. From 1981-84 he was the Organ Scholar at King’s College, Cambridge University, during which time he studied organ with Jean Langlais in Paris. The first British winner of the Tournemire Prize at the St Albans International Improvisation Competition, he also won the first prize in the International Improvisation Competition at Paisley. Subsequently David held positions at Hereford, Truro and Gloucester Cathedrals.

David’s schedule includes more than 60 concerts a year, spanning several continents. Deeply committed to making organ music vibrant for future generations, he enjoys giving pre-concert lectures designed to make organ music more accessible to audiences. In addition, he teaches at Oxford and Cambridge, frequently serves on international organ competition juries, and gives masterclasses at colleges and conservatories across the U.S. and Europe.

David Briggs is also a prolific composer and his works range from full scale oratorios to works for solo instruments. He has recorded a DVD, and 29 CDs, many of which include his own compositions and transcriptions. For more information, Please visit: www.david-briggs.org.

Those who know me know that there is one and only vendor from whom I will buy coffee beans. That vendor is George Howell (http://terroircoffee.com/).

Those who know me know that there is one and only vendor from whom I will buy coffee beans. That vendor is George Howell (http://terroircoffee.com/). And there was The Man, sitting at the counter, drinking an espresso macchiato. I said to the girl, "I'll have what he's having." I greeted George, and we chatted about ... well, coffee. I spoke with disdain about a certain large competitor that, George informs me, is opening one new store a day in China. Growth at the expense of quality. Or as George unforgettably put it: "If you cover the whole world, you're flat as a pancake."

And there was The Man, sitting at the counter, drinking an espresso macchiato. I said to the girl, "I'll have what he's having." I greeted George, and we chatted about ... well, coffee. I spoke with disdain about a certain large competitor that, George informs me, is opening one new store a day in China. Growth at the expense of quality. Or as George unforgettably put it: "If you cover the whole world, you're flat as a pancake." On Thursday, October 21st, one of the greatest sopranos of the 1950s and '60s, Virginia Zeani, celebrates her 85th birthday.

On Thursday, October 21st, one of the greatest sopranos of the 1950s and '60s, Virginia Zeani, celebrates her 85th birthday.Maybe the following story will give a sense of how much Madame Zeani has meant to me. About five years ago, I was talking to members of the church choir that I was directing. I spoke of Richard Tucker. One of the paid soloists, an opera major at a prestigious school in Boston, said, “Tucker? Who was Tucker?” I then spoke of Zinka Milanov. Another soloist of the same credentials said, “Well, I don't know the old-time singers that well.” “Old-time” singers?! If she was “old-time,” how could I even talk about the singers I really cared about: Battistini, Caruso, Ponselle, Gigli, Tagliavini, Pertile?

Enter Virginia Zeani, who actually studied with Pertile, who actually sang with Gigli and Tagliavini! Her career lasted long enough to sing with Pavarotti and Domingo when those guys were still young and at the height of their powers. She could speak intelligently about Pertile or Pavarotti or anyone in between, because this wasn't a topic that she read about in school – she lived it. She sang with these greats. And they were fully aware of her greatness, as well. No less than Richard Bonynge said that the most beautiful soprano voices he ever heard, apart from his wife Joan Sutherland, were Kirsten Flagstad, Virginia Zeani, and Renata Tebaldi.”1

I really can't explain to you why I, who was born in 1971 and who was educated in the public schools of Revere, Massachusetts, felt drawn to the technique and musicality of the singers on the scratchy 78 records. If I could explain it, you would then know how healing it was to be able to discuss these artists with a woman who understood that technique, and who used it herself. In Romania, she studied with Lydia Lipkowska2, a famous Russian soprano and a court singer to the Czar of Russia3. Lipkowska sang with Caruso. From there, Zeani went to Italy (March, 1947) to study with one of the great vocal technicians of the time, and one of my idols, Aureliano Pertile.

I apologize if this tribute comes across as being very personal, with many repetitions of the words “I” and “me.” However, I cannot overestimate the fulfillment and, indeed, healing that I received from Madame Zeani. For if it was difficult to find contemporaries with whom to talk about Tucker, with whom could I talk about Pertile? With Madame Zeani I could talk about him.

I could also talk about the great conductor, Tullio Serafin, who asked Zeani to replace Callas in a production of I Puritani. That evening in January of 1952 was Zeani's Florentine début and her first performance in an important Italian house. That same night, her dear teacher Pertile was on his deathbed. The dying maestro said to a mutual friend, “I am happy for her; now will begin her great career.”4 And it was at that very performance that she first met the greatest singer-actor among post-Chaliapin bassos. His name was Nicola Rossi-Lemeni. She would later marry him.

I could also talk about Italy's greatest vocal coaches of the 1950s: at La Scala, Antonio Narducci, Edoardo Fornarini, Leopoldo Gennai, Antonio Tonino; at the Teatro dell’Opera in Rome5, Enrico Piazza, Vincenzo Marini, and the great Luigi Ricci.6

I could also talk about the cast of Giulio Cesare at Madame Zeani's La Scala début on 10 December 1956. Cesare was Rossi-Lemeni. Tolomeo was Mario Petri. Sesto was Franco Corelli. Curio was Plinio Clabassi. Nireno was Ferruccio Mazzoli. Cornelia was Giulietta Simionato. Achillas was Antonio Cassinelli (who later married Maria Chiara).

I could also talk about Alfredo Kraus. “I was very good friends of Alfredo Kraus. … He was a special one. You know, I heard him at his début. And we spoke only one month before he died [in 1999. His début was in] 1956, in Cairo. And I was there.7 … We were good friends, he and his wife and I. … Rosa died two years before him. During our last conversation, he said that he didn’t know how he would ever get over Rosa’s death. I knew exactly what he felt. After Nicola died, I thought, 'How will I ever get over it?' … We sang probably 200 performances together, in Lucia, in Puritani, in Manon, in, what else, Sonnambula, in — my God! — in Traviata — loads of Traviatas.”8

I could also talk about Gigli and Pertile. And believe me: there are few things in life I enjoy more than talking about Gigli and Pertile. But how often can I talk with someone who actually worked with them? “I had my début in L’Elisir d’Amore with Gigli in 1950, in Cairo. I was 24, and he was [60]. … And he had a very big belly, and at the end of the opera he had to embrace me, no? Because in L’Elisir d’Amore Nemorino embraces Adina. And Gigli said to me, “Cara mia, sai che cosa ci divide? Quaranta chili e quarant’anni! Senza quelli, ti potrei abbracciare con molta più facilità.” [My dear, do you know what separates us? Forty kilos and forty years! Without them, I could embrace you much more easily.”] … [Gigli] was a very nice man and very full of spirit, full of, how can I say, sense of humor. … Gigli and Pertile were, in a way, like Pavarotti and Domingo. … Different vocalities. [But] both of them went directly to the heart. The voice is only an instrument. But you have to give to this voice the heart. The tears. The joy. The poetry. They are everything, you know. It’s what makes the singer. The great singers, they were very few. If someone has a voice, many people think, 'Wow, great voice.' But if that’s all it is … I didn’t sing for the money. I didn’t sing for the glory. I sang because I loved what I did. … You know, Gigli was the maestro of caressing the sound. It was a caressing voice, a velvet voice, but at the same time based on the words. ...

“Pertile was humble. Was nice. Was delicate. In the lessons I never heard him saying something negative about anybody. Sometimes he had the tenors who came there and said, 'Maestro! Look what a high note I have!' And he would say, 'Yes, but you have to have something leading up to the high note.'”9

“I first got to know Gigli’s singing when I was a child in Bucharest, listening to his recordings. I began studying voice at age twelve-and-a-half. My love was divided between the records of Gigli and those of Pertile.”10

“The purity of [Gigli's] sound is absolutely without equal. … You see, his passaggio is perfect, never forced; he maintains the sound in the same position from the beginning to the end, with the intensity of the vibrato and the diminuendos.... The high notes and low notes are in the same position, with intensity and big legato. This is the science of singing. I’m sorry to say, today the science is lost. They try to sing opera like in a musical. No, I’m sorry, I don’t accept it. ... You see the simplicity that he uses in the sound, not forcing and not diminuendo but with a great sadness in the sound. So colorful. His voice loves and caresses everyone around him. Nobody else could have done these things, maybe only Pertile but in a different sense. … [Gigli's] phrasing is unique. It originates from the heart and is guided by the sustaining of a miraculous breath. … It is incredible to hear singers like Aureliano Pertile and Beniamino Gigli, who — in different ways, with different voices — imbued so much emotion into their singing. Later there was the splendid Corelli, whom I will never forget hearing in Adriana. Everyone was in love with him. But the manner, the agility, the color, the flexibility of the sound of Gigli — they are difficult to find in another singer. … [T]he Gigli that I knew in person [in 1950 was] still brilliant, still full of enthusiasm, even if the breath wasn’t always perfect in those years. I suffer, because I have these beautiful sounds in my memory, but I cannot transmit them to everybody. … How can you write a book about Beniamino Gigli? It is not a book about Gigli. It is a book about the history of singing. It’s a book about the maximum of love that people have for music.”11

Not long after my first conversation with Madame Zeani, I realized that there was almost no limit to the amount of great singers from the past about whom we could talk about. Equally voluminous would be a discussion of all the great students whom Zeani nurtured since joining the faculty of Indiana University in 1980. (I believe she holds the record for the most Met Competition winners and finalists by one teacher.) Here is where we get into the territory of Zeani's incredible generosity and warmth. She is more than a voice professor to her students – she is mother hen, friend, adviser, consoler, encourager, muse. “[W]hen the students come to me … I bring out the maximum that they can do. I would like that everybody is 1,000 times better than me. You know, the students who study with me, they know what is the Belcanto, they know what kind of vocalises to do, they know in which voices to believe, because I teach these things.”12

Madame Zeani made an interesting observation about the students of today. As compared with the living conditions of the struggling student of the 1930s and '40s, today's students don't have to “suffer” nearly as much. “Not that I wish suffering upon them,” Zeani was quick to explain.13 However, the suffering of the singers of past, somehow, comes through in their singing. This, according to Zeani, is what is missing in the singing of today.

I like to contrast the following two quotes, because they seem to describe two completely different people – the first perhaps some famous star that certainly you would never meet in person, the second perhaps some beloved aunt.

“Who before [Virginia Zeani] succeeded in offering a more complete interpretation [of Violetta in La Traviata]? At least in my opinion, neither Caniglia nor Cigna on the one hand, nor Dal Monte nor Pagliughi on the other — besides the fact that physically, Zeani dominated [the competition] as the most seductive interpreter of Traviata that was ever seen on our Italian stages.” – Davide Annachini14

“A sweeter, kinder person never existed.” – Charles Handelman15

So which was she? Was she one of the 20th century's finest belcantisti, the greatest Violetta of her time, or of all time? Or was she a friend who counseled me after my divorce, whom I could call anytime I wanted, who – like a close family member – could be depended on for sweetness and for total candor, both in great quantity?

She was both.

1 Opera News, September 1999

2 Lipkowska’s name is sometimes spelled Lipkovska or Lipkovskaya. The reference books cannot agree on her dates; she was born in either 1880 or 1882 and died in either 1955 or 1958.

3 It must have been the last czar, Nicholas II, who reigned from 1894 to 1917 and was murdered in 1918.

4 Bruno Tosi, Pertile: Una Voce, Un Mito (Venice, 1985), pp. 179f.

5 Ms. Zeani was prima donna assoluta there for nearly a quarter-century.

6 Luigi Ricci (1893-1981) worked with Puccini for eight years and with Mascagni for thirty-four while an Assistant Conductor at the Teatro Reale (now called the Teatro dell’Opera) in Rome. Other composers with whom he was associated included Respighi, Giordano, Zandonai, Henze, and Pizzetti. Among the many great conductors with whom he worked were Marinuzzi, Gui, Panizza, Serafin, and De Sábata. He was coach, accompanist, and close friend to Beniamino Gigli. Ricci authored two books (Puccini Interprete da Se Stesso and 34 Anni con Pietro Mascagni). He collaborated on the musical direction of forty-two films and numerous recordings with RCA. Starting at age 12 (!), Ricci accompanied the voice students of the legendary Antonio Cotogni (a favored baritone of Verdi). Young Ricci began taking meticulous notes on the 19th-century traditions that Cotogni passed on to him. Decades of continued note-taking resulted in the four-volume Variations, Cadenzas, and Traditions, a precious compilation – still in use – of the cadenzas of famous 19th-century singers, conductors, and composers.

7 The opera was Rigoletto.

8From the interview in L. Ciampa, The Twilight of Belcanto (hereafter “Twilight”)

9Twilight

10Ciampa, A Beniamino Gigli Commemoration (unpublished) (hereafter, “Gigli”)

11Gigli

12Twilight

13Conversation with the author (2006).

14 Davide Annachini, liner notes to Virginia Zeani, Vol. II (Bongiovanni, Il Mito dell’Opera, ASIN: B00009L1TR). English translation by L. Ciampa.

15 E-mail to the author (August, 2003)

Her tone fused brightness with depth, and long past the age when most singers retire, Davenport still commanded a tone that was large, steady, and glowing. What turned out to be her final local appearance was in Brahms’s Alto Rhapsody at Boston University in 1986, her voice still radiant and expressive, the legato technique recalling the golden age of singing. Her students in more recent years report that during lessons Davenport still rang out commandingly over a three-octave range. She was an imposing and elegant presence at concerts, and her unsparing views were never a secret because this was a voice that carried. (Boston Globe, June 20, 1997, p. D16)Notice that Dyer used form of the word “command” twice in one paragraph. This was appropriate. There was something commanding about Mary. Yet despite her aristocratic upbringing, I always found her to be an affectionate, gentle person uninterested in keeping up false appearances. She just was someone who relished quality, in people and in things. If she had a clock, it was a beautiful clock. If she had a dress, it was one her seamstress made for her. Her library contained the best books, in the best editions. It was as if her stomach couldn’t quite take anything, or anyone, that didn’t exude quality.

We discussed old-time singers quite often. She’d talk about hearing recitals by Gigli and Tauber in London, or singing Aïda with Helge Roswaenge. “He was about sixty at the time,” Mary remembered. “Amneris, of course, comes on the stage right after Celeste Aïda. He sang the aria so beautifully that when I came on, I almost couldn’t sing.”

We discussed old-time singers quite often. She’d talk about hearing recitals by Gigli and Tauber in London, or singing Aïda with Helge Roswaenge. “He was about sixty at the time,” Mary remembered. “Amneris, of course, comes on the stage right after Celeste Aïda. He sang the aria so beautifully that when I came on, I almost couldn’t sing.”